Vigyan Bhavan & Kempinski Ambience

10 - 14 February 2014

Delhi, India

Blog Archives For Blogs Tagged Blog

A great deal of the World Congress on Agroforestry, held in New Delhi, focused on business: How to link smallholders to markets? How to make agroforestry profitable? How to engage major corporations? How to guarantee social and environmental sustainability while making money?

Some of the liveliest discussions involved high-profile executives and entrepreneurs, including a panel with Howard Shapiro, chief agricultural officer of Mars Inc.; Bernard Giraud, president of Danone’s Livelihoods Venture, Tristan Lecomte, founder and CEO of the Pur Project; and the noted Indian entrepreneur and sustainable-business advocate Ranjit Barthakur. In breakout sessions, we explored the viability of trees as crops, looked into biofuels as a reliable energy source and discussed quantification of environmental services.

A consistent message was that farmers can’t do it alone, especially if they’re also growing food for their families. Building successful agroforestry systems, requires scientific expertise, business savvy and access to markets, robust policies and infrastructure, and NGO support to advocate for farmers and help with training and facilitation. It’s a team effort, and it takes a lot of resources.

Read full blog

(published on the website of SIANI, Swedish International Agricultural Network Initiative)

—

Related Story:

Business – smallholder relationships: true commitment or false promises?

Landscape in Tanzania. Photo by Paul Stapleton/ICRAF

In order to realize implementation of a landscape approach, a dynamic combination and interaction of factors is involved. At a Landscape session during the World Congress on Agroforestry, discussions focused on key areas involving actual implementing case studies, need forsynergies between mitigation and adaptation in policy, innovative community-driven institutional platforms, and governance.

A comparative study looking at 191 Integrated Landscape Initiatives in Latin America and Africa showed that while in both regions the motivation for adopting landscape approach are sustainable environmental protection, enhancing food security and agricultural productivity; in Latin America, where the practice has been conducted for a longer time than Africa, incentives go further to include reducing negative agriculture impacts.

In both places, the initiative involves stakeholder groups, government, producers, marginalized groups and non-governmental organizations inside and outside the landscape. Groups studied cited tangible outcomes including improved skills and governance structures as success factors and lack of funding, proper infrastructure, proper policies, government and private sector involvement as challenges to a landscape approach.

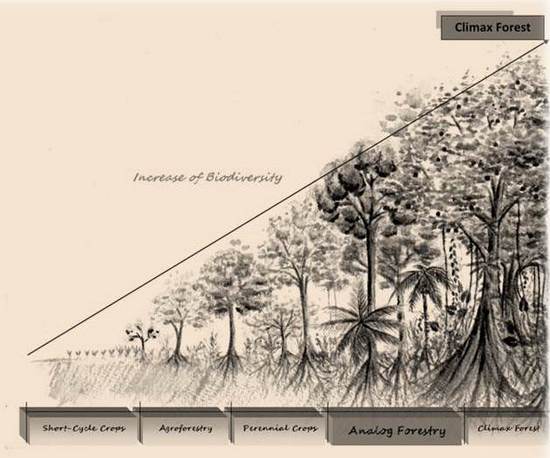

In Sri Lanka, effort is underway to reclaim degraded land where forest has been cleared for tea and coffee farming since the 1800s. Challenges to deal with currently as the project is implemented include quick win commercial ventures and lack of native planting material.

When looking at policy frameworks that implement a landscape approach, emphasis was made on the need to synergize mitigation and adaptation as opposed to looking at the two streams separately. The example of environmental service in Suba, Ethiopia was used to illustrate the domino effect between the two approaches. For instance, failure to adapt to drought and flooding in the region creates a knock on effect on mitigation as communities are forced to move into productive forest areas where they clear the forest for increased farm productivity. On the other hand, failure to mitigate leads to high carbon emissions that in turn lead to either drought or flooding, making it harder to adapt. To synergize, multifunctional landscape level actions are needed.

In Eastern Uganda, innovation platforms that comprise ‘multi-stakeholder arrangements, innovation networks, coalitions or public-private partnerships’ have been adopted as institutional frameworks to foster community cohesion and collective action; yielding positive effects of increased livestock, tree cover and raised income levels.

In Mexico, a pilot study is testing the use of agroforestry as a conservation measure in protected areas, which would require reforms in political administration and land tenure for the most part.

To provide governance structures that are manageable, one presentation showed innovative territorial governance known as The Model Forest Landscape Approach as it is being carried out in 5 countries across six regions. Benefits of this particular innovation at a landscape level have provided resilient social infrastructure, effective experimentation, demonstration and practical knowledge sharing tools. It has also promoted regional dialogue as well as public – private partnerships and growth of local business.

Ensuing discussions at the session made it clear that the feasibility of landscape approaches largely hinge on favorable policy frameworks driven by political will and active involvement of all stakeholders; including specific targeting of the private sector, a move that has potential to inject new innovation and funding.

By Elizabeth Kahurani

Communications Manager, Environmental Services & ASB Partnership for the Tropical Forest Margins

Related links:

Landscape approach allows business to share risks and benefit

On the closing afternoon of the World Congress on Agroforestry 2014, participants from South Asia, East, West and Southern Africa came together to plan on how to dramatically scale up the use of trees in cropping and grazing lands of smallholder farmers across the world.

Dennis Garrity, Chair of the EverGreen Agriculture Partnership and UN Drylands Ambassador, emphasized the need to “embed these ideas into the hearts and minds of the ‘hard-core aggies’.”

Once the idea has been taken on by organizations working daily with farmers in mainstream conventional agriculture, large-scale adoption will become achievable, said Garrity.

Representatives from across Africa and South Asia heard about successes and the progress made so far in establishing partnerships and demonstrating agricultural approaches that integrated trees into farm fields.

To date, about a hundred thousand women farmers in Malawi are growing Gliricidia sepium for fodder for their livestock and nutrients for their soil. And emerging partnerships in East Africa are easing the sharing of knowledge and experiences with systems like conservation agriculture with trees.

But in order to share the benefits of these approaches further, the group made a unanimous call for greater collaboration and partnerships with groups such local radio stations, education institutions and NGO consortiums at both a national and global scale. By working with institutions such as these, science-based solutions such as EverGreen agriculture can be shared more widely, adapted locally and extended to farmers, often by farmers across enormous scales.

For each region, many methods and opportunities to take this scaling up further were identified, and the partners at the event drafted actions plans.

“In India in particular, the opportunities to accelerate scaling up are extensive. And we have exciting opportunities in many of Africa’s regions,” said Garrity.

While funding was raised as a challenge in some regions, the meeting agreed that with organizational commitment, you can move forward with what is available.

In Dennis’s words: “Good ideas, and good programs are the basis for good funding”.

“It is all about partnerships, bringing science to development, and shaking hands with development partners as we move forward together.”

By Alice Muller

EverGreen Agriculture Partnership Manager

Related stories

We need Steve Jobs’ in agroforestry

Where good science and the art of innovation meet

—

For more information: www.worldagroforestry.org

Evergreen Agriculture web site: www.evergreenagriculture.net

Email: d.garrity@cgiar.org and a.muller@cgiar.org

Social Media training at the World Congress on Agroforestry

Someone once told me, we can do all the science we want, we can do all the agricultural research for development we want, unless if our findings get “out there”, the research is a useless spending of public funding.

And “getting it out there” is not just publishing in scientific journals, but “getting it out there” through open access, giving each and everyone access not only to our research findings, but also to the insights of our research process, inviting discussions already during the research process itself.

In that philosophy, social media plays an increasingly important role, as we have proven in our CGIAR research in the past years.

And this goes also for conferences like the World Congress on Agroforestry: For us, the communications team, conferences are not a goal, they are a means. A means to advocate for our causes, a means to include of remote participants into the onsite discussions and presentations, and also a means to build capacity amongst participants, our partner organisations, and youth in the use of online media and social media, for science communications.

Core to the social media outreach at #WCA2014 was a group of 135 social reporters from all over the world. Around 110 social reporters supported us remotely, and 25 of them were onsite.

Fifteen social reporters followed a two-day social media induction course just prior to the Congress. Many of them came from the “traditional media”: the print media, radio or TV, and had little exposure to online media, leave alone, social media.

One of them is Beena Kharel who just started her new job as a Communication and Research Uptake ‘Specialist’ for The International Water Management Institute (IWMI) in Nepal

Coming from a traditional media and journalism background, Beena wrote the following blogpost about her first “adventures in social media wonderland”, the challenge faced in using a plethora of social media tools, and the challenges to “communicate about science without being a scientist”.

My First Social Media Ramblings

New to online science communication? “Please don’t lose your heart!” This is what seasoned social reporters told me in the corridors of the World Congress on Agroforestry (WCA) in Delhi.

The can-do camaraderie generated amongst online communicators saved the heart of CGIAR online newbies, like myself, who were ready to learn and contribute to live reporting (or social reporting) from the Congress.

It was heartening to see how a small group of dazed professional communicators, assembled as online newbies, transformed themselves into spontaneous online communicators in a couple of days.

Peter Casier, the WCA2014 social media coordinator, guided us through the process: “I know several of you struggle real hard to find a sense, a flow, and a schwung in your blog post. But your blood, sweat, and tears is worth it!”, he exclaimed the first day. And as Peter loves people who love social media, he guarded over us like a hen guards its chicks.

Transforming into an online communicator

Peer learning and interaction with communities of practice boosted the secret drive of the social reporters at the WCA2014. The group of trainees, based in Asia and Africa, wanted to assimilate into the world of social media for a professional cause. They knew adoption of a fast-emerging medium will also fetch them more dollops to butter their daily breads.

These communicators and online writers, of course, were the quintessential lot with adequate skills they have honed over the years, with a fair share of stumbles and successes. Above all, they had the love for reaching out to tell more stories in the interest of humanity.

Some of them, overdosed by traditional communications, were trying to rehabilitate into professional bloggers and hashtaggers.

Casier, an online communication expert, offered buckets of wisdom in a two-day social media boot camp set-up as a precursor to the Congress. It was in the boot camp I had met half a dozen enthusiasts from the CGIAR family dedicated to communicating science.

Social media is one thing. Social reporting is a different thing altogether.

Live tweeting and blogging from an international Congress expanded into four plenaries and six breakout sessions with a range of topics—from application of science to business impacts of agroforestry…

It was nerve-wrecking.

A social media reporter from Europe quipped: “It is like picking up a sachet of an instant Nestle kaffee in a place without taste buds for the original coffee.”

Blogs and Twitter, the main official online media, chosen for social reporting for the Congress could have been somewhat new and awkward for some professional communicators. Some needed a little push to rekindle their interest in instant communication.

A few others (like me) with no science background had to muster courage and energy only to listen to the scientists who tried to explain their findings in serious languages in less than 10 minutes in a packed auditorium. Breathless!

After the painful listening was over, the question was: What to do with the learned ramblings they had uttered during the training, which we had so dutifully jotted down or captured in gadgets? Chase a panelist on tree fodder and animal nutrition after a breakout?

Thank You, done! But a young scientist from the Indian state of Mizoram must have found my question how the villagers in rugged terrains do to get their daily supply of animal fodder too simplistic to answer. He described the landscape of North-East India instead. After the third attempt, he politely said that he would improve his presentation in the future, as I clearly did not get it. My pain: How to ask the right question on a subject you hardly know anything?

Look for audience in help? A nice tip! I tried when a female audience urged the panelists to walk extra miles to advocate their findings for actions and criticized their shy and neutral approach. Content for a blogpost?

Follow a vocal audience! Even a better tip! I grabbed a Filipina scientist-turned-activist who is married to an Indian. She wanted the scientists to become advocates and more, something like God! Content for a blogpost?

Social media for Scientists

To be or not to be an advocate is an individual choice. Not all scientists have the aptitude and incentives to opt for trendy communications. Publishing in scientific journals is one thing; publishing online in blogs or on Twitter or Facebook is another game.

More scientists, especially from the social spectrum, are appearing online to storify their findings. This is helping sell science better, inform funders about the good use of their money and create the impact of researches, say senior managers of agroforestry institutes.

Dr Sandeep Sehgal, assistant professor on agroforestry based in Jammu of India, acknowledges his student who opened his eyes to social research and the importance of online communications to get the message across. He had contributed “Scary Trees” for a blog competition in the run-up to the Congress.

An increasing number of scientists, researchers, science writers and publishers with a knack for instant, crisp and convincing narration have joined social communication channels to bridge the gap between ‘serious’ scientists and ‘fluffy’ communicators. This has given a fresh spin to innumerable campaigns—seen online even on casual clicks—to generate awareness about natural resource management, its effects on daily lives and the future for humanity.

What will happen to our dear traditional forms of communications then? I believe they will continue to bring sanity to online media!

Blogpost by Beena Kharel, Communication and Research Uptake Specialist, The International Water Management Institute (IWMI), Nepal

Preface by Peter Casier, WCA2014 Social Media Coordinator

Photo by Daniel Kapsoot (World Agroforestry Centre)

Coffee plantations are expanding fast at the cost of disrupting ecological systems. Coffee Agroforestry System (AFS) seem to have positive impact on environmental services; or do they?

Kodagu, located in the Western Ghats in India, produces 2% of the world’s coffee. The Western Ghats is one of the top ten biological hotspots in the world; over 137 species of mammals and 508 species of birds can be found here, including a sizeable population of majestic elephants.

Over the last 30 years, coffee has expanded tremendously in the region to the detriment of the forest and its dwellers. The intensification of coffee cultivation is also leading to the removal of shade trees which is directly linked not only to better growth of coffee but also to numerous ecological benefits. Water is another critical resource affected. The main rivers which provides water all over Southern India, originate from these coffee areas of the Western Ghats.

The tree composition of this coffee landscape has been affected by changes in farmers’ management practices, such as irrigation to stimulate coffee mass flowering, or introduction of exotic tree species (mainly silky oak) for timber production and pepper.

Speaking at the World Congress on Agroforestry WCA2014, Philippe Vaast, an eco-physiologist from ICRAF & CIRAD, said trees are important not only for providing shade but also for providing a microclimate for other organisms, but farmers are not adept at managing shade.

“The right amount of shade is important for coffee; too much or too little is harmful. This manipulation of shade is not done well or understood by farmers. A lot of work needs to be done in this area. ”

A project undertaken by ICRAF and partners studied for 3 years how the change in tree cover from predominantly native tree species to exotic species affected the water dynamics in coffee AFS of the Kavery watershed of Kodagu district, the most important coffee district of the region.

The research threw up a mixed bag of results: the native trees were better than exotics in terms of providing optimum shade and a better environment for coffee growth, but the exotic trees were superior in recharging aquifers.

According to Syam Viswanath, a scientist at Indian Council of Forestry Research & Education (ICFRE), two important factors have to be taken into account for coffee agroforestry system: yield and quality.

“The kind of tree a farmer finally plants on his farm is a result of many factors: growing speed, maintainability, robustness, economic value or simply its attractiveness to an elephant!”

By Nitasha Nair

Ms Nair is a Senior Communication Officer with the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) – India

—

For more Congress blogs, please visit http://www.wca2014.org/blog/

For even more agroforestry-related blogs, please visit http://blog.worldagroforestry.org/

Congress on Twitter: #WCA2014!

Farmers in Talensi, Ghana, regenerate their trees. Photo by Tony Rinaudo

The agroforestry system known as Farmer Managed Natural Regeneration (FMNR) is spreading rapidly and widely, but can this be explained by good science?

Science guides us on optimal species to promote, plant spacing, pruning methods, soil fertility impacts, moisture levels, annual crop yields and much more.

Science also explains important concepts relevant to FMNR, such as apical dominance (i.e. why the central stem of a plant grows more strongly than other side stems) and why such rapid growth from tree stumps is possible. But the reason why FMNR is being adopted on a very large scale is not primarily because we got the science right.

I believe FMNR is being adopted by tens of thousands of farmers in dozens of countries in Africa and Asia because it is a low cost, rapid and flexible tool which is in the hands of farmers.

FMNR enables farmers to respond quickly to their ever changing economic, environmental and social reality. They adapt this flexible tool, happily sacrificing ‘optimum output’ for the much more desirable outcome of yield/income stability.

Resource-poor, risk-averse farmers have to survive and want to thrive in a highly risky social-environmental-economic reality. Failure can literally mean disaster, even death so they opt for stability of yield/income over time rather than maximum yield in some years.

In 2013, Dr. Richard Stirzaker from the CSIRO in Australia wrote the following:

“I have followed the development of Farmer Managed Natural Regeneration (FMNR) since its very beginning in Niger during the early 1980’s. Thirty years later, independent scientists have hailed FMNR as contributing to the greatest positive transformation of the Sahel. I agree.

FMNR is a counter-intuitive idea. Traditional agroforestry has always tried to specify the ultimate tree-crop combination and arrangement that maximises complementarily. FMNR is based on a naturally regenerating suite of tree species, each growing where they are because they have demonstrated an ability to best exploit a specific niche and overcome prevailing constraints. The farmer then thins and selects from this ‘template’ that nature has produced. Farmers derive their livelihoods from cropping around the trees, cutting browse for animals, producing construction poles and firewood. The contribution each of these options make towards food security depends on current trees density, rainfall, availability of labour and the prevailing prices for the different products, providing food and income stability in a very variable environment.

I do not think that any research program, no matter how well funded, would have come up with the idea, because it expertly combines the subtleties of location specific tree selection with farmer specific opportunities and constraints.”

This is not an attack on good science, nor does it nullify the need for science to guide the targets that FMNR should move towards. It is a call to give greater emphasis on the real needs of farmers, to include them in the scientific method and even, sometimes, to follow their lead.

More information on FMNR can be found here: Farmer_Managed_Natural_Regeneration

A brief video explanation on FMNR can be found here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E9DpptI4QGY

By Tony Rinaudo

R & D Advisor, Natural Resources

Food Security and Climate Change

World Vision Australia

tony.rinaudo@worldvision.com.au

Apples. Photo by Wolfgang Lonien

As Steve Jobs used to say, “People don’t know what they want until you show it to them.”

Agroforestry has what people want and need, in both the developing and developed world. Trees that improve crop yields, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, provide nutritious fruits, fodder for animals and fuel. The challenge lies in getting agroforestry adopted on a huge scale.

Eternal optimist Dennis Garrity, UNCCD Drylands Ambassador and former Director General of the World Agroforestry Centre addressed participants at the final day of the Congress saying “people will come to you if you have the right products.”

“Yes, we’ve had our failures,” said Garrity. “But these have helped us to produce dynamite products in agroforestry.”

In France, farmers are producing wheat with walnut trees. Agroforestry is increasingly being seen in Europe as a means for reducing the greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture. Agroforestry systems are being developed for the American corn belt.

In Niger, over 4 million hectares of croplands are now dominated by fertilizer-fodder-fuelwood trees through what is known as Farmer Managed Natural Regeneration (FMNR).

It seems there is a menu of agroforestry products – fertilizer, fodder, food and fuel trees – that farmers can select from, but how can this knowledge be better transferred from scientists to the grassroots level. Garrity says we have failed to get the hard-core aggies on board. “How many agronomists are in the room today?” he asked, to which a few scattered hands were raised.

“We need to reach out to the aggies, they need to know about what we are doing and they need to be coaxed.” Garrity is working hard to achieve this through Evergreen Agriculture which he describes as a brand that connects agroforestry with hard-core ‘aggies’ to scale-up trees on farms.

“African farmers are showing how trees can be successfully integrated into cropping systems. When will we catch up and fully deploy their insights?”

But as I alluded to earlier, Garrity is an optimist. He believes we are beginning to see a trend which will be at the heart of a truly sustainable planet: the ‘perennialization’ of agriculture.

“If we do our jobs well, we will see that perennialization is the key to meeting the new Sustainable Development Goals.”

Agroforestry science and development can make a crucial contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals which will soon replace the Millenium Development Goals. But this contribution can only be made through a massive effort in up-scaling agroforestry across the world.

According to Garrity, we need global maps of agroforestry, a global agroforestry assessment and a global plan for up-scaling agroforestry. Additional staff will be needed to link science with development and we must not forget the holy grail: genetic information on tree species.

An “upcoming global revolution in agroforestry up-scaling” is before us, says Garrity. We have to demonstrate that agroforestry really does have the products that millions of farmers across the world want and need.

“Be ambitious,” said Garrity told Congress participants. “We need more Steve Jobs’s in agroforestry.”

Photo by Wolfgang Lonien

Men carve a pattern from a paper template. Jepara, Central Java, Indonesia. Photo by Murdani Usman/CIFOR via Flickr

People in Europe buy furniture made from Indonesian timber. They want to know that the wood is harvested legally. New EU import rules will start soon. For farmers in Indonesia, it looks like more and more paperwork with no guarantee of new markets and better income.

The European Union has agreements called Forest Law Enforcement, Governance, and Trade (FLEGT) between itself and countries that grow tropical timber. New FLEGT rules from January 2014 will have an effect on regulations in Indonesia that govern how the 5 million or so smallholding timber growers on Java in Indonesia operate.

These smallholders produce most of the timber for the USD 1 billion worth of annual furniture exports. Their operations are already regulated to greater or lesser degrees along the entire length of the value chain, from choice of land and seedlings through harvest, sale, transport and manufacture to export. There are a number of organizations that support, or purport to support, smallholders navigate the maze of regulations and charges, adding further layers.

The set of rules through which FLEGT is implemented in Indonesia is called Sistem Verifikasi Legalitas Kayu (SVLK/Timber Legality Verification System). SVLK requires third-party auditing and licensing of timber legality for all timber products and the relationships between timber producers, craftsmen and the manufacturing industry.

As well, the Ministry of Forestry regulates ‘distribution notes’, which provide species-based verification, typically for timber from food-producing trees like rambutan and mango. There are also ‘self-usage distribution notes’ for timber from State land, which are based on the territory or respective administrative area. And then there is the one that smallholders are most familiar with: the Surat Keterangan Asal Usul Kayu or SKAU; this is both species- and territory-based verification for timber not produced on State land.

“The implicit challenge is to tailor licensing and regulation differently for different modes of production within a system that is already facing financial difficulties, especially at the smallholder level,” said James Erbaugh of the University of Michigan, who presented findings from his team’s research at the World Congress on Agroforestry in New Delhi, India, on 12 February 2014.

As it is, the SKAU requires a smallholder to report to the closest village head or forestry official who has been certified for SKAU approval. This official then conducts a physical examination of the timber to be transported. Then, the smallholder must complete a Location Verification form, which requires proof of land ownership. The verification receives a serial number upon publication and six copies of it must be delivered to specific officials and offices.

The research team observed that there was a mixed level of enforcement for this verification. Timber that was destined to go across the district boundaries often included the document, while timber that stayed within the district was less often accompanied by the document. They were unable to determine the extent to which the document was completed and enforced.

“It would probably be more effective to tackle the legitimacy of SKAU certification rather than relying exclusively on trying to verify that farmers and the wider industry were complying with it,” said Erbaugh. “The need for the whole SVLK system is not because of an absence of the verification of legality but because of the lack of legitimacy. Addressing this might circumvent certain problems that SVLK is bound to face.”

How the lack of legitimacy might be addressed the researchers didn’t say. Presumably through the provision of evidence to the EU by the Indonesian Government. Perhaps most importantly, the researchers did not look at whether new SVLK licenses have actually increased market access to new EU markets for local growers or not. If the system isn’t working now, will it work in the future? Probably only with serious reform at all levels.

By Robert Finlayson

—

Follow the Congress on Twitter #WCA2014 for live updates!

A team of nine individuals from different agroforestry-related organizations worldwide will spearhead the formation of an organization that will facilitate cooperation and knowledge-sharing in this area.

The organization, the brainchild of the World Agroforestry Centre and the Indian Council of Agricultural Research, is expected to establish and manage an international secretariat which will coordinate activities in support of its members.

Interested founding members have been given up to three months from the close of the World Congress on Agroforestry to express their interest, through an email provided as a.temu@cgiar.com.

Other draft objectives of the organization include convening forums at different scales (global and regional) that promote agroforestry research and practice, actively engaging in international policy forums and debates that relate to agroforestry land use and providing platforms for its members to collaborate for mutual benefits.

The organization will also strive to promote publication and sharing of agroforestry research results and successful adoption and implementation.

“This organization aims to bring together national and regional agroforestry associations, research organisations, farmer groups, NGOs, corporations, universities and any individual with the common interest of transforming livelihoods and landscapes through agroforestry for a sustainable future,” said August Temu, one of the volunteers to the working group committee.

The Drafting Committee of nine distinguished individuals will develop and refine the Union’s charter. This Committee immediately sat down for its first meeting and agreed to work to an ambitious timetable. The charter they will work on will be opened for comments on 2 April. This period will conclude on 12 May, after which the Drafting Committee will formulate a final version for adoption by the founding members on 2nd June. This date is auspicious: it marks the opening day of the European Agroforestry Congress, to be held in Cottbus, Germany.

The members of the Drafting Committee are August Temu, Roger Leaky, Patrick Worms, Shibu Jose, Gregory Ormsby Mori, Mohan Kumar, Rosa Mosquera-Losada, Gillian Kabwe and Sumit Chaturvedi.

“In order to form such an international organization, you must have a charter in place, which is a legal document. We already have a draft charter ready with us,” said Temu.

It is expected that the organization will be in place later this year.

They welcome your contributions and comments, so drop them a line!

By Isaiah Esipisu & Patrick Worms

Development agencies and researchers have long assumed that rural women are victims. Not only of climate change but also nearly everything else. New research says these assumptions are without basis.

According to Bimbika Basnett, a researcher with the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), the premise that women are victims of climate change rests on tenuous assumptions and weak empirical evidence. What’s more, there is a tendency amongst people researching gender and agroforestry to tabulate data that has been separated into male and female data and draw far-reaching conclusions from it.

“In a way, it’s welcome that women are being discussed in the climate-change area,” she said. “But when you look at the assumptions that the discussions are based on, they are wrong. They can lead to negative outcomes.”

The general argument is that poor and disadvantaged people are more vulnerable to climate change. Women are lumped into the category without question. However, men might be poor and vulnerable, too, and distinctions between the genders might be hard to correlate with vulnerability to climate change.

Yet in climate-change debates, the idea of women as victims is used to introduce wider issues of inequality. And because women are supposedly victims they can be mobilized to affect change. Basnett questioned where ideas like this came from and what sort of influence they had.

Recent research showed that there were two oft-repeated claims circulating in the sector: 1) Women are 70% of the poor; and 2) they are 14 times more likely than men to die in natural disasters.

There is no basis for either of these claims, says Basnett. ‘Data in developing countries is hard to get and of poor quality so how can someone reliably calculate the global percentage of poverty by gender? Second, there is no clear definition, anywhere, of what exactly is meant by “poverty”. Being poor in one country is different from being poor in another.

“Gender and poverty are usually separate issues in most countries and not exclusively the province of the rural poor. For example, in urban areas gender issues can be magnified, such as here in India, where female sex-selective abortion is more common in cities among wealthier people than in the countryside among the poor.”

Basnett also traced the source of the claim that women were 14 times more likely to die in a natural disaster. It was first aired as an anecdote in a workshop on natural hazards in 1994 and repeated without question thereafter for another decade.

Both these assumptions persisted even though they were wrong and no one had seen the original data.

“I think the uncritical acceptance of these statements, and the unquestioned “women are victims of climate change” argument, has been driven by the motivation to ensure that women and unequal power relations are included in policy discussions about climate change,” she said.

“People use this position to seek sympathy and strategic coalitions with those who privilege investing in women as a form of smart economics.”

This kind of thinking has negative effects, such as limiting the understanding of gender to stereotypes of women and men. It also weakens the credibility of gender research and encourages the implementation of policies that reproduce gender inequalities.

Basnett’s advice, not surprisingly, is that facts and figures should be investigated and not assumed. Second, there should be sound gender analyses conducted and, third, the approach used should be rights-based rather than instrumental.

Perhaps then women will be afforded the respect they deserve.

By Robert Finlayson

—

Related story

Gender is a many-splendoured thing

—

Follow the Congress on Twitter #WCA2014 for live updates!

Smallholder farmers in Sumatra and Kalimantan in Indonesia are often reluctant to plant improved, high-yielding clonal rubber trees in their agroforestry systems. Dudi Iskandar from Agency for Assessment and Application of Technology, Indonesia, set out to figure out why.

According to Iskandar, in Sumatra and Kalimantan, 7 million farmers depend for their livelihoods on rubber, which is mostly grown in a traditional mixed farming system with unselected ‘jungle rubber’. With this system, the expected annual latex yield will only reach 590 kg/ha, far below rubber monocultures which can produce up to 1310 kg/ha over the same period.

This situation can be improved by applying a system called Rubber Agroforestry System (RAS), developed and introduced by the World Agroforestry Centre . Unlike the jungle rubber system, in which seedlings are unselected, RAS uses clonal rubber. With RAS farmers produce more rubber, continue to harvest other different products from the agroforestry system, while at the same time maintaining the landscape’s environment sustainability.

Despite the benefit it offers, however, the adoption of RAS is still limited.

“When it comes to clonal rubber, lots of farmers have difficulty in identifying it,” said Iskandar. “It is true that they really want to improve their systems’ productivity, which they realize can be achieved by using clonal rubber. But often they were fooled by seedling sellers, who stamp ordinary seedling as clonal rubber,” Iskandar told the congress.

“Later, when these trees don’t produce the desired yield, it makes farmers doubt clonal rubber.”

This is one factor that hinders the adoption, along with other factors such as incentives, income level, the establishment of demonstration plot and land-size.

Iskandar’s study, which looked at 223 rubber farmers in Jambi and West Kalimantan provinces, also found that farmers with incentives and higher incomes were more likely to adopt RAS, because buying clonal seedlings needs capital.

To support adoption, the establishment of demonstration plots is considered important, because farmers need to see the proof of the benefits of RAS.

“These are smallholder farmers who don’t have the liberty of taking many risks, so before they adopt it, they need to be sure that it actually works,” Iskandar explained.

“Therefore, RAS demonstration plots is the precise way to do so because it provides a visible ‘success story’, letting farmers see the evidence for themselves,” he pointed out.

Iskandar added that RAS is considered as a good option to increase yields, specifically when the farming area is narrow.

Furthermore, Iskandar recommended that the government provides more support to smallholder farmers, such as access to information, credit, loans, as well as incentives in the form of provision of genuine clonal seedlings, fertilizers and pesticides.

“There is also the possibility to build the incentives farmers are longing for into payments for environmental services (PES),” he added.

By Enggar Paramita

—

Follow the Congress on Twitter #WCA2014 for live updates!

“Ask not what your country can do for you, but ask what you can do for your country!”, said John F. Kennedy in his inaugural address.

Would large companies have similar ideas when buying produce from smallholders? “Smallholder, don’t ask what I can do for you, but what you can do for me”?. The dynamic has to be more complex than that.

Consumer behavior, certification and green-washing

When “northern” consumers started to get conscious about the impact THEY are having by choosing their basket of goods, businesses started to get cold feet. “We have to please them, what shall we do?” Suddenly, many started embracing Certification, Organic, Fairtrade, etc. NGOs like Rainforest Alliance and UTZ Certified mushroomed to get a slice of the cake which was to be made from this opportunity. Businesses were happy that they could team up with someone to get a green vest. Some called this Greenwashing, others are claiming truly sustainable benefits for both the environment and humans.

“Has certification failed?” Tony Simons, director general of ICRAF, asked several high-ranking corporate officers at the World Congress on Agroforestry 2014. Answers were mixed. Some said that even with the best of intentions the inhumanly hard market would not even allow a 5 – 10% premium to be granted to smallholders. Others asked the question “Well, what do you get for your money?” and stated that “Certification is buying guilt from rich consumers”; an interesting thought. But are you capable to evaluate the promises? In most cases not. “If a smallholder can live in poverty being certified, it has failed” Dr. Howard Shapiro, Chief Agricultural Officer MARS Inc., said. I agree.

What I see as key to the problem are constraints in two fields: international standards and consumer attitudes, particularly with regard to education. About the former: Inconsistencies between labels are very big today. There is a need for a set of internationally recognized indicators a company has to comply with before it can call itself “green”, “sustainable”, “environmentally sound”, etc. A situation that the Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL) and HAFL in Switzerland have addressed with an FAO mandated project called “Sustainability Assessment of Food and Agriculture systems” (SAFA). Regarding consumer attitudes, let me give you an example: a beloved person of mine is fanatic about eco-friendly products. But does she know what is behind this term? It takes a huge amount of time to get behind the curtain. Time we don’t have in the “North”. Once the standard set of indicators is a necessity for businesses to get a product labelled, we can start developing equally-standard courses at schools to teach the upcoming generation what the label in the store actually means.

What about science and Public-Private-Partnerships (PPP)?

We need to ask ourselves: “What are the questions we need to ask better” when we bring the researcher into the game. Researchers funded by public money are required to create knowledge for the public good. But when it comes to Public-Private-Partnerships, are businesses not misbalancing Justitia’s scale, are scientists not losing their position as the upholders of neutrality, the ones you can rely on when in need of objective information? We must ensure that science can hold up its noble position as the objective conscience of society. Furthermore, someone must stand up to the duty of informing smallholders about possible risks and consequences that come along with promised-to-be long-term partnerships with the big guys. Who is responsible for that: researchers, governments, extension workers? Or is it at the end of the day really the corporate responsibility? And if so how can we assure that is being implemented? Brings us to the ultimate question I want to ask: “Private sector: the beauty or the beast?”

After all, win-win situations and long-term partnerships are not only a nice-to-have, but a must for sustainable development of both businesses and farmers livelihoods. I think the IAASTD report brought this message across in a quite unbiased way.

Blogpost by Christian Andres/FiBL (Frick, Switzerland) – christian.andres@fibl.org

Photo courtesy Disney

Nikki Pilania Chaudhary, the winner of our ‘Special Prize from the Social Media Jury’,

receives her prize from Dr.Tony Simons (Director General, World Agroforestry Center)

In the run-up to the World Congress on Agroforestry (#WCA2014), we ran a blog competition. The purpose was to provide agroforestry researchers, practitioners, students and farmers a platform to showcase their projects on our blog. We also used this opportunity to encourage people to discover the power of blogging -and social media as a whole- as powerful online publishing and discussion tools. In the process, we also guided people into “the art of blogging”.

The online public could vote for each blog entry, and leave comments, stimulating online discussions on the topics our contest entrants blogged about.

In one month, we received 47 blogposts from 19 countries (India, Morocco, UK, Kenya, Indonesia, Comoros, Cameroon, Burkina Faso, Moldova, Bolivia, Nigeria, Kyrgyzstan, Uganda, Canada, Nepal, Sweden, Eritrea, Vietnam and Switzerland).

These contest entries received a total of 23,991 online votes, and 2,262 comments, which was way beyond our expectation. This success showed how eager people were to publish and interact online.

The power and joy of social media

It was also encouraging to see how many competition entrants told us, this was actually the first time they wrote a blogpost, and how they enjoyed discovering the ease of publishing and the speed in which the blogposts “traveled” through the online media. Many were surprised about the amount of people who read the entries: over 35,000 people.

Here are some excerpts we received from our competition entrants:

When I circulated information about my blog to the Agricultural Research Service Scientist forum of ICAR & Agricultural extension as well as Animal Nutrition Association, they got introduced for first time to the concept of Blogging. Some wish to write now. It may go viral!

I am happy to see, it is making some impact. (…) (Our) scientists were largely ignorant about this till today, despite good publicity made through different channels.I am enjoying blogging!

(This) is a kind of game changer for me!! I’m inspired so much & wish many get inspired too! So, I have uploaded it on all of my networks! hope it would help many to think social media a bit more productively, like blogging!!

– Dr Mahesh Chander, Principal Scientist & Head, Division of Extension Education, Indian Veterinary Research Institute

The blog post competition is well received by all here at ICAR/NARS and I hope this will be trendsetter….

–Sridhar Gutam PhD, ARS, Patent Laws (NALSAR), IP & Biotech. (WIPO) – Senior scientist (Plant Physiology) Central Institute for Subtropical Horticulture

It was quite fun participating in this competition. Though I have lost all hopes of winning since I can check the number of votes other participants have got, (…) it was fun indeed, but I learnt so many new things in the process.

– Dr Sandeep Sehgal – Assistant Professor, Agroforestry, Sher-e-Kashmir University of agricultural Sciences and Technology

And the winners are:

While each and every single blog post described an interesting project. There was quite a variety in writing and presentation styles. The posts all plugged into different areas of public interest.

Needless to say that for us, each and every blog post is a winner. After all, the joy is in competing, and going through the process of writing to blogpost.

However, the online public decided in its 23,991 votes. And here are the #WCA2014 blog contest winners are:

1st place:

Entry #21: 5,104 votes

Let’s endorse Fodder Banks for reducing pressure from forests and women drudgery

by Dr.Shalini Dhyani, Scientist, CSIR-NEERI (A scientist from Nagpur, Maharashtra, India)

2nd place:

Entry #7: 5,089 votes

Forestry and Farming a way through: Aloe Vera the green gold amongst us

by Angesom Ghebremeskel Teklu (A social entrepreneur from Asmara, Eritrea)

3rd place:

Entry #30: 3,852 votes

Can we enhance the productivity of our forests through agroforestry?

by Dr. Chandra Shekhar Sanwal, Indian Forest Service, DCF Uttarakhand cadre (A scientist from Dehradun, India)

4th place:

Entry #16: 2,280 votes

Shift of a Paradigm: A Micro Initiative Towards Agro-Forestry

by Manish Kumar (A student from Navinagar, Uttar Pradesh, India)

5th place:

Entry #14: 1,331 votes

Women, livestock and fodder trees in Central Himalayas

by Dr Mahesh Chander, Principal Scientist & Head, Division of Extension Education, Indian Veterinary Research Institute (A scientist from Izatnagar, India)

The prize of appreciation by the social media jury:

A special honorable mention, and the prize of appreciation by the social media jury was awarded to:

Entry #3: 1,229 votes (with an average score of 5/5):

Agroforestry: Attracting youth to farming and transforming Rural India

by Nikki Pilania Chaudhary – Chaudhary Farms (A farmer from Pilibhit,India)

In their nomination, the social media jury wrote the following justification for Nikki’s for prize of appreciation:

Nikki is a young female farmer. This was her first blogpost, and she writes passionately about a crucial topic, urging educated youth to pick up farming in rural areas. Nikki also attended the social media training and is part of our social reporters’ team.

Excerpt from Nikki’s blogpost:

“Farming needs intelligence, good know-how, and lot of professionalism to carry out complex agricultural operations. We need to change our attitude and perception towards farming and I request youth to come up with a green thumb and not to underestimate farming. Agriculture has the potential to provide them with not only a very good income but also the chance to transform rural India.”

The prizes:

These six authors will receive a certificate and a signed copy of “The Trees for Life,” a new book to launched at the Congress.

Dr.Shalini Dhyani wins the first prize: a shiny new Apple iPad tablet.

Congratulations everyone!

A special thanks goes to all of you:

… our blog contestants. You took the opportunity and dared to experiment.

… our online voters. Your votes are the encouragement for our competition entrants to continue experimenting in social media

… all who left comments on the blog entries. You enticed a real online discussion in a critical but positive way, while showing your appreciation to the bloggers.

We hope each and every one of you continues to experiment with social media as a powerful publication and discussion tool.

Well done all!

Picture courtesy Daniel Kapsoot

Earthworms. By Yun Huang Yong via Flikr

If the holy grail of agroforestry is to optimize crop yields and productivity while maintaining the provision of ecosystem services, it turns out it might be a good idea to humour the kings and queens who live underground—nematodes, earthworms, termites and other creepy crawlies that do their work in the soil.

I attended the WCA2014 session on ‘Biodiversity and Agroforested Habitats’ yesterday morning (12 Feb 2014). The session was chaired by Edmundo Barrios, ICRAF’s scientist on Land health, and was surprisingly, or perhaps not so surprisingly, packed full.

The amount of research covered and the level of collaboration between various universities and the World Agroforestry Centre within the six presentations was staggering.

Much of the science was beyond me, but as a lay person whose home is in one of the biggest coffee-growing areas in Ethiopia, my interest was immediately piqued by the research presented.

For example, Hairiah Kurniatun reported on shade, litter, nematodes, earthworms, termites and companion trees in coffee agroforestry in relation to climate resilience. The researcher from University of Brawijaya in Indonesia explained some effects of cropping patterns in coffee agroforestry systems on the abundance of parasitic nematodes. Radopholus love the cocktail of coffee and banana trees but do not particularly like gliricidia (a multipurpose leguminous tree). Unfortunately, neither do earthworms.

In particular, their research showed that a mix of Coffee plus gliricidia plus avocado created lower instances of the parasitic abundance, but add mahogany and the nematode numbers almost doubled. Beautifully useful information from research.

The presentation by Mattias Jonsson, titled ‘The effects of shade, altitude and landscape composition on coffee pests in East Africa,” had one of my favourite slides, on how to decide whether shade trees are useful for control of white stemborer, coffee berry borer and lacebugs in coffee.

What was more surprising is the research by Vivian Valencia and colleagues that shows that cash crops like coffee are better for the environment, and more robust to climate variability than food crops. You see, coffee agroforestry systems are intermediate between forest and monoculture coffee in many aspects of above- and below-ground biodiversity and related functions.

For the farmer, however, the balance of positive and negative aspects of diversity needs to be understood in relation to processes such as nutrient and water uptake, slope and topsoil integrity, and harvestable yield.

Coffee agroforestry is considered a promising alternative to conventional agriculture that may conserve biodiversity while supporting local livelihoods. Another study that finds that coffee agroforestry might in fact be better for biodiversity than crop monocultures and pasturelands. Whenever appropriate, strategies and policies should trigger the conversion of coffee monocultures and pastureland into coffee agroforests, thereby sparing forests and reforesting tree-less agricultural land.

I’m sure for countries whose incomes include large amounts from these cash crops, this is very good news indeed, but what does it mean for food crops?

Edmundo Barrios in his talk argued that recommendations of what types of tree densities, arrangements and species maintain essential ecosystem functions provided by soil biota in agricultural landscape is essential. Furthermore, identifying, quantifying and mapping host spots of biological activity and ecosystem services should aim to develop local soil health monitoring systems to evaluate ecosystem service provision performance. This, said Barrios, would allow rural communities, environmental/agricultural institutions, and local governments to prepare for negotiations related to payment for ecosystem services.

I couldn’t help but wonder, in a world where money talks, whether researchers can quantify this information in dollar terms, especially for cash crops like coffee, rubber and cocoa.

Because when Wall Street’s interest is piqued, then perhaps the kings and queens of the soil will survive, and ultimately, ourselves.

By Akefetey Mamo

—

Follow the Congress on Twitter #WCA2014 for live updates!

Philip Dobie delivering a truly inspirational and philosophical talk about the way forward for agricultural science to create impact. Photo by Sinead Mowlds (co-author).

Research and Development (R+D) has been around for a long time; every serious big business has an R+D unit. Looking at the context of agricultural research, there was a slight but significant change in the wording lately: R+D became R4D—Research FOR Development. Suddenly, scientists are expected to not only develop the solutions, but also apply them to attain development. To meet this huge challenge we need nothing less than a fundamental change in paradigm: R4D has to become R-IN-D, meaning Research in Development.

From top-down to bottom-up

Extension was essentially born as a top-down approach; Scientists were expected to develop solutions and put them on the shelf. Extension workers would buy the solutions and apply them in the farmers’ context. Change has led scientists to increasingly opt for the bottom-up approach. They apply concepts like Farmers-to-Farmers Extension (FFE) and Volunteer Farmers Training (VFT) among others. All these terms can be categorized as types of Rural Advisory Service (RAS). Quite a promising approach if you ask me. Even more so as there is a Global Forum for Rural Advisory Service (GFRAS), which acts as an umbrella for RAS approaches around the world.

However, many scientists are still opting for the top-down approach; recently for example, the First International Conference on Global Food Security was held in the Netherlands. Before I went there, I asked myself: isn’t food security essentially a local problem? At the conference itself I asked myself why scientists were spending huge amounts of resources to develop complicated models in order to calculate worldwide yield gaps for different crops, only to conclude with statements like “OK, well, our model works well or doesn’t work at all under these and those circumstances”? Is it because they are afraid of going out to that bumpy real world to do something with their proper hands that truly has impact?

The fact is that food security is a local problem, and only bringing together multiple local solutions can solve the problem of “global” food security. Maybe they will call it “First International Conference on Local Food Security” next time.

From R4D to R-IN-D

So here I was at session 6.3 of the World Congress on Agroforestry 2014 entitled “The science of scaling up and the trajectory beyond subsistence”. Quite an ambitious title, but it hits the spot! After Ann Degrande and Evelyne Kiptot had set the scene with inspiring case-studies, the chair himself took over. Steve Franzel delivered a remarkable talk to raise the quality level of the session even more.

The title of this blog was taken from the chair’s speech; let me repeat: “It’s not about best practice, but best fit”, indicating that best practices are always site-specific.

It is only when you have the general picture (through meta-analyses and the like) that you can break it down to the local level again taking into account the very circumstances you are dealing with (in various dimensions). Today, many case studies are available. The trick is to stir the pot and cook a new recipe from it that brings us forward.

But that was just the beginning. One of the most inspiring, pleasing, mind-soothing yet challenging and highly philosophical speeches I have ever heard at a conference was the one given by Philip Dobie. He drew a mind-blowing picture of Research IN Development, which would enable us to make science a more rapid learning process by shortening feedback loops as inherent part of innovation cycles. In order to get there, we need to take two main steps:

Firstly, mindsets of scientists and donors have to change in the same way as the wording (from R+D to R4D). Donors funding R4D projects expect you to “have impact” in your research. This impact does not come with a publication in a journal with a high impact factor like Science or Nature. After all, paper remains paper. No, the true impact is in many cases still missing. Farming systems research is taking a first step into the right direction, making methodologies more multi-dimensional thus holistic. Systems are complex and therefore unpredictable. If agricultural systems are so, the development we want them to undergo is at least as complex!

Secondly, we need to design research projects to be much more of a learning process in order to shorten these feedback loops! We have to design our projects to be more complex, integrating social and bio-physical science under the same roof in new forms of institutions. For that, Philip Dobie says, we have to take the courage to say “No” to our donors sometimes. That is, if they have not yet understood the direction research needs to go to truly have impact.

After all, impact is what donors want. It is also the desire of farmers, and hopefully the preference of researchers working in R4D.

By Christian Andres

Researcher in Tropical Production Systems

FiBL (Frick, Switzerland)

—

Follow the Congress on Twitter #WCA2014 for live updates!

In rural Malawi, when people get infected with HIV, they increasingly rely on forest resources for medicines and fruits. How can agroforestry take the pressure off forests?

“Agroforestry can provide HIV-AIDS-affected people with some of their most basic needs such as firewood, traditional medicines and fruits,” says Joleen Timko, a researcher from the University of British Columbia.

In Malawi, which has a predominantly rural population that depends on forests for food and fuel, an estimated 10.8 per cent of the adult population is living with HIV/AIDS.

Forest resources in the country are already depleted. “If these resources are further depleted, those affected by HIV-AIDS could suffer immensely from decreased stamina, increased vulnerability to further infections and other diseases, and greater food insecurity,” says Timko.

Timko has been researching how the disease has impacted on forest resources in Malawi.

“In different phases of the disease, affected people’s dependence on forest resources changes,” she explains. “For example, when people are sick (known as the morbidity phase) they rely heavily on medicinal plants to treat side effects of HIV-AIDS such as shingles and diarrhea.”

“Medicinal plants are so depleted now in the forests of Malawi, that people are collecting these from the forests of nearby Zambia and Mozambique.”

During this morbidity phase, people also increase their use of wild fruits and honey to improve their health and detoxify the effects of AIDS-related drug treatments. Fruits may also be in higher demand at this time because people at this stage lack the energy to collect firewood that is required to cook other foods.

HIV/AIDS sufferers also rely more on bushmeat for alternative income when they are sick.

Following AIDS-related deaths, households increase their use of timber to build coffins, for funerals and ceremonies. Forest lands are also being converted to cemeteries.

Timko asked local people in Malawi about how agroforestry could help to alleviate some of the burden HIV/AIDS places on them.

Among the interventions they mentioned were domesticating medicinal and fruit trees, planting fast-growing trees for firewood and creating community herbaria for traditional medicines. They would also like to see training provided on sustainable harvesting of medicinal plants as well as on honey production for food, medicine and income generation.

Agroforestry could go a long way towards protecting the forest resources of Malawi and providing important resources that HIV-AIDS-affected communities desperately need.

By Kate Langford

Globally, about 842 million people are undernourished – about 12% of the population – and more than 2 billion suffer from micronutrient deficiency, or “hidden hunger,” according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

This is a great improvement from 20 years ago, when 19% of people in the world were going hungry. Yet as poverty declines, demand for food rises. With the global population expected to grow from 7 billion today to nearly 10 billion by 2050, demand for cropland will be ever-higher, intensifying the pressure to clear forests for agricultural expansion.

The irony is that – although further research is needed – several studies have suggested that forests play a key role in nutrition and food security. For example, a study of 21 African countries, using data from health surveys of 93,000 children aged 1-5, found that children living close to forested areas tended to have more nutritious diets and consumed more fruits and vegetables. At the World Congress on Agroforestry, which I am attending this week in New Delhi, a full session was devoted to exploring the links between tree cover and nutrition. (…)

Read the full post by Swedish International Agricultural Network Initiative (SIANI)

Blogpost by Matilda Palm, a post-doctoral researcher in the Department of Energy and Environment, Chalmers University of Technology, and a member of the Forest, Climate & Livelihood Research Network (Focali). She is participating in the World Congress on Agroforestry as part of a collaboration between Focali and the Swedish International Agricultural Network Initiative (SIANI) around the theme.

Once every five years we celebrate the role of tree-based systems in human prosperity with an international congress. The World Congress on Agroforestry 2014 in Delhi, India, kicked off the second day of thematic sessions today with a programme on “Science Advances in Agroforestry”.

Although the Congress is multi-stakeholder by design, after the Policy prelude, the science segment sits in the middle between the business day and the development day as a better bridge for impact.

There are six million scientists in the world but less than 0.1% of them would likely described themselves as an agroforestry scientist. Although since Albert Einstein said “Science is a refinement of everyday thinking” perhaps everyone is a scientist in one form or another.

But all scientists (sensu stricto) and indeed all 7.2 billion humans alive today rely in one way or another on tree products and services – and therefore in a way rely on agroforestry scientists. Yes, give yourself a clap.

Also give a generous clap to the two keynote speakers that triggered our high quality science day:

Tatiana Sa from EMBRAPA in Brasil first led the captivated audience through a contextual history of agroforestry science finishing with why it is highly relevant today in the soon to be post-2015 era.

This was followed by Kate Schreckenberg’s (University of Southampton) expose of 21st Century Challenges and how social and biophysical agroforestry science can help unravel the conundrum of the planetary and societal boundaries. Kate also reminded us that we learn as much from our research failings as we do from our successes, and therefore we need to embrace them and publicish them more avidly.

The word “Science” is derived from a similar Latin word which means “to know” or “knowledge”. Overall three types of science were presented today in plenary and in 12 exciting parallel sessions accompanied by 350 posters;

Type 1 Science is where we have enough knowledge and we just need to extend it.

Type 2 Science is where we still have significant knowledge gaps that need filling. And…

Type 3 Science is where by testing different ways of extending knowledge we develop a co-learning framework on second generation research problems and impact delivery.

Perhaps the biggest delusional trap we all have to watch out for is believing that innovation and quality evidence is confined to Type 2 Science, especially of the purely academic variety.

We also have to avoid the outdated belief that it is local research and then repeated actions that lead to adoption and impact at scale when rather it will be research at scale that leads to local solutions and impact.

Type 1 Science does not have all the answers either in the belief that efforts to achieve greater impact will come from previous and currently successful innovations and interventions by just scaling them up. More likely the underlying reason for unrealised development impact is due to failed assumptions.

More specifically, it is a failure to list, test and/or adapt the assumptions upon which the design and implementation of development programmes were based. Through simple, linear and mechanistic planning the interactions between political, social, economic, biophysical and ecological systems have been ignored. These systems are not only complex but also dynamic, diverse and unpredictable. It is enigmatic therefore that we attempt to use simple and single knowledge solutions to solve complicated and complex problems.

Lastly, the issue of “communications of science” came up repeatedly in the sessions. Here we must all remember that knowledge does not diminish just because it is shared, and we need to be careful that the science of agroforestry does not become a foreign sort of secrecy.

Blogpost by Tony Simons, Director General, World Agroforestry Centre

Picture: Scientist in the World Agroforestry Centre seed bank

Coffee agroforestry system in Sierra de las Minas, Guatemala. Trees shade can be measured with MAESTRA, a light-interception model. Photo via Jonathan Cornelius/ICRAF

Kira Borden held the audience spellbound at the World Congress on Agroforestry 2014 as she described how radar can be used to map the roots of trees. Showing a slide of a team with picks and shovels bent double next to a tree, the University of Toronto PhD student said that using “ground penetrating radar (GPR) is easier than digging to find its roots”, up to now the conventional method.

“We can now conduct non-intrusive below-ground studies. Roots contain more water than dry soil and reflect back the radar beams, which create two dimension vertical profiles.” Knowledge of roots is particularly important in determining below-ground carbon; roots contain 20-40% of total tree biomass.

Borden was speaking on 12 February in the ‘New tools and paradigms’ session of the third ever global gathering on agroforestry. Chaired by ICRAF’s Tor Vagen, himself the developer of a method to map soil carbon and link it with remote sensing (see ICRAF Geoportal), the session profiled six innovations.

Fabien Charbonnier spoke about how to measure shade, a key issue in agroforestry systems as they strive to find optimal spatial arrangements and densities of trees. Reporting on MAESTRA, a three dimensional light interception model, he said that light “could now be assessed as a continuous variable.” Applying MAESTRA to coffee fields in Central America, he found that the effect of shade trees, Erythrina poeppigiana, was larger than the crown projection.

Staying in Central America, Bruno Rapidel reported on what happened when CAF2007, a numerical model for shade coffee systems, was combined with a participatory approach which involved farmers in designing agroforestry systems with multiple requirements and the interactions of several tree species.

“We interviewed 600 smallholder farmers producing premium coffee on small plots in an area of high erosion due to sleep slopes,” said Charbonnier. “The erosion is a threat to a new hydroelectric dam. So we wanted to know how many trees farmers needed to maximize production of coffee and payments for ecosystem services – received for reducing erosion. Involving farmers in the CAF2007 model helped us to explore a system that the farmers would accept and put in place.”

In a similar vein, Claude Garcia from ETH Zurich, spoke about using on-line role playing to understand farmers’ choices in the mountains of the Western Ghats in India. “Wicked problems are those with multiple stakeholders and many uncertainties. The answer is often processes rather than solutions.”

A wicked problem in the Western Ghats is the trend for farmers to remove of native trees and replace them with full sun coffee, a change which damages the ecosystem services, mainly water, delivered by the tree clad hills. Garcia’s on-line game, played by the farmers, gave them information on the coffee yields and the livelihood and biodiversity levels that resulted from their decisions. “We were able to generate a library of strategies and to create a decision tree.”

Finally, describing a non-technical approach, Clement Chenost of Moringa Fund spoke of agroforestry as an innovation in itself, which is still new to the private sector. Moringa Fund, the world’s first investment vehicle dedicated to agroforestry, currently has eight investors which have put in a total of EUR50 million. Chenost said agroforestry is highly profitable in the long run – producing timber, biomass, cash crops, carbon money and more, and that social risk could be lowered by well-designed out grower schemes. However, it was a mark of how complex investors find agroforestry that it took three years for Moringa to raise this sum.

“Industry is specialized, segmented, dominated by monoculture and in need of consciousness changing,” said the investment fund manager. “And agroforestry is complex with several species and markets and hundreds of thousands of smallholders. We need to communicate that this complexity can be managed.” Moringa Fund is advised by research organizations ICRAF, CIRAD and IRD.

By Cathy Watson

Head of Programme Development

World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF)

—

Follow the Congress on Twitter #WCA2014 for live updates!

100 year-old Caragana hedge; trees break the speed of fast-moving air. Photo by Doug Viste via Flikr.

In temperate regions, agricultural practices integrating leguminous trees and food or forage crops can sharply reduce overdependence on chemical fertilizers, and improve yields. Tree boundaries also shield pastures against fast-moving winds.

Discussing his findings at the ongoing World Congress on Agroforestry, Anthony Kimaro, a researcher with the World Agroforestry Centre, shared evidence where sufficient nitrogen was transferred from a Caragana tree (Siberian peashrub) shelterbelt in Canada to forage crops, thus replacing the use of fertilizers.

“It is important to note that the overuse of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer to meet the requirements of food and forage crops species contributes to environmental problems such as nitrate leaching to groundwater and enhanced greenhouse effects through N2O emissions,” Kimaro told a session at the Congress.

During the study, Kimaro with co-researchers planted fodder crops near a caragana shelterbelt to determine the amount of nitrogen transferred from the trees to crops.

The scientists later found out that plants close to the shelterbelt row received significantly higher percentage of nitrogen compared to those further away. “The nitrogen received was within the optimum application rates for these crops, meaning there was no longer any need to apply nitrogen based fertilizers,” he said.

According to Shibu Jose of University of Missouri Columbia, this is one of the sustainable solutions agroforestry can offer to existing global challenges.

According to Jose, other challenges that can be solved by agroforestry include food security, energy, water scarcity, greenhouse gases, loss of biodiversity, diseases and invasiveness.

“Agroforestry is the way to ‘bullet proof’ farms in the face of climate change,” he said.

A different study done in Chile by Alvaro Sotomayor, from Sede Biobío, Instituto Forestal, Concepcion, Chile, found that apart from fixing nitrogen into other crops, the trees reduced the velocity of wind, which is a disturbing factor in the Aysen temperate region of the country.

“The results obtained show that the trees managed under silvopastoral systems modified some ambient climatic parameters. The main parameter that was modified by the trees was average wind speed,” he told the session on Temperate Agroforestry at the Congress.

Sotomayor’s study evaluated the effect of Pinus contorta plantation, managed under two designed silvopastoral systems, in altering climatic parameters such as wind speed, wind chill, relative humidity, ambient temperature and precipitation that reached the ground, and its effect on livestock and prairie production.

By Isaiah Esipisu

—

Follow the Congress on Twitter #WCA2014 for live updates!

Drylands are home to almost one in three people in the world and support half of the world’s livestock. But when we think of drylands, Chile is not a country that immediately comes to mind.

However in the ‘Mediterranean’ semi-arid region of Central Chile lies the Espinal. This savannah-like landscape covers 3.8 million hectares and is of great importance to small and medium scale farmers who graze their livestock under a canopy of native ‘espino’ or Acacia caven trees.

As Alejandro Lucero explained during his presentation at the Congress, the Espinal is a dryland agroforestry system under threat. “Overuse for grazing and timber extraction has left much of the Espinal highly degraded,” he explained.

Lucero believes conserving and rehabilitating this silvopastoral system could lead to social and environmental sustainability for farmers in Central Chile.

“The Espinal is one of the most important resources in semi-arid Chile,” said Lucero. It not only provides fodder for livestock but firewood and charcoal, fruits and seeds that produce flour, cosmetics and medicines.

The Acacia caven trees in this agroforestry system protect livestock from extremes of heat and cold. The trees also benefit the soil; contributing to nutrient cycling, adding organic matter and increasing the availability of moisture.

While the system is protected under the Native Forest Law, forest management plans currently fail to optimize its development and maintenance as a sustainable agroforestry system.

Lucero hopes that renewed interest and investment in the Espinal will lead to a global analysis of optimal pasture production, livestock and tree product harvesting that can sustain the system over the long-term.

By Kate Langford

—

Download Alejandro Lucero’s abstract

—

Related articles

Root-Bernstein, M and Jaksic F (2013) The Chilean Espinal: Restoration for a Sustainable Silvopastoral System. Restoration Ecology 21 (4): 409-414

Rewilding Chile’s savanna with guanacos could increase biodiversity and livestock

By Kate Langford

Chocolate aficionados may have cause to worry, as some farmers in Sulawesi, the largest cocoa bean-producing island in Indonesia, are thinking of abandoning cocoa farming to grow other commodities.

Indonesia is the third-largest producer of cocoa in the world, behind Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. Sulawesi, the K-shaped island located in the eastern part of the country, is responsible for 67% of Indonesia’s cocoa production. Around 2.2 million smallholder farmers in Sulawesi grow cocoa on 1.5 million hectares, supplying most of the national production.

In recent years, farmers in Sulawesi have faced many problematic issues, and they are losing the appetite for cocoa cultivation.

A study presented at the World Congress on Agroforestry by Janudianto from the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) said the key problems in Sulawesi are high rates of pest and disease attack, limited access to high-quality germplasm, and poor farm management.

“These factors have lowered production, causing farmers to start replacing cocoa with fruit trees, pepper, rubber or oil palm,” said Janudianto.